Have your (otherwise pretty advanced) students ever complained that they don’t understand authentic speech, like films or native speakers they meet in the street? If so, read on.

In the attempt to help my in-company students better understand their British and American colleagues and customers, I’ve been teaching a 30 hour long listening course that is based on recent research into what vital modes of listening training are absent from most contemporary coursebooks. I’m quite happy with the outcomes of the course (the students show evident progress and the feedback I’m getting is very positive).

In this post I’ll

- describe a generic ‘listening lesson’ plan that I’ve used in every class (also, in the Lesson plans section of this blog you will find five listening lesson plans that follow this procedure). Update. See also materials for my IATEFL’15 presentation on the same topic.

- share some further tips that I’ve learnt since I started developing the course last February.

- give links to two indispensable tools and explain how to use them

- Also, I’ve put together a lot of links to actual listening materials which, crucially to this approach, have subtitles – in order to make this post a bit more readable, I’ve published them in a separate post.

So far I’ve taught 13 ninety-minute lessons out of 15 in the course I’m currently running. In the first one I introduced the students to some of the reasons why listening is problematic (summarizing them in one phrase, students need intensive practice decoding features of connected speech; you can find out more in this post and in the book by John Field linked to there). In the subsequent 12 lessons we targeted a range of accents, including American, Canadian, Australian, Scottish and non-native speaker (Israeli). Last a Friday we did Indian accent, which my students and managers have been begging me to target ever since I joined the company last December. I’ll write up all those lesson plans and publish them in this blog later on. All of these lessons (apart from the introductory one) follow the following pattern.

A generic listening lesson plan.

Levels. I teach each lesson in three different groups (their levels are B1+/B2, B2/C1 and B2+/C1), and I’ve also used some of the materials in a strong pre-intermediate group (they’re finishing the course, so they are around B1), but the pre-intermediate students did struggle.

Lesson length: 90 minutes

Preparation:

- Find an interview that has subtitles (pick and choose from the links in this post) and is appropriate for your students (that is, does not contain topics you don’t want mentioned in class – though I’m pretty relaxed about that and actually find stories shared in authentic interviews a welcome break from distilled/PARSNIPSed coursebook audios.

- Go through the transcript and locate a couple of general interest questions and interesting answers (two 3-minute extracts will do).

- Print out the transcripts for those extracts (one copy for each student in class).

- Alternatively, come back to my blog in a couple of weeks – I’ll write up my lesson plans that I’ve created for the course by then – and use my plans and materials.

- If your interview is not on youtube.com, install the (free) tool described at the end of this post

Materials: A print-out of the transcript for each student. For lower levels, a gapped transcript of the first part of the interview.

Procedure. The course that I’m teaching specifically targets listening skills, so there are no discussion tasks (I did use some in the first couple of lessons but they really don’t fit this format) and I hardly teach any vocabulary. Nevertheless, classes are generally lively, because the students do get plenty of opportunities to share what they’ve heard and scaffold each other, and there’s also usually lots of banter (and moaning!) about the peculiarities of accents that we’re working on. Apart from the first class, which was a general introduction into listening decoding difficulties, the remaining classes are completely independent of each other (also, there were some students who joined the group a few weeks into the course and they’re working fine, so the first introductory class doesn’t seem to be that crucial).

As I mentioned above, in general, I structure each lesson in this course around an unabridged interview. A generic lesson is structured like this:

0. Pre-listening. Sometimes I start off with some kind of prediction / activating schemata tasks, and sometimes we just delve straight into listening.

1. Gist & initial diagnostics (~10 minutes). The students watch an extract from the interview (normally, a reply to one question, which generally lasts around 3 minutes. I try to go through the interview before the lesson and pick some genuinely interesting stories). Having watched the extract, the students share what they’ve heard in pairs or groups or three (3 mins). I listen in and then conduct brief feedback (3 mins), establishing the main facts and the main points the students are still uncertain about, but without spending too much time, without correcting anything the students have misheard or letting the students listen for the second time. I also ask the students how challenging they found the speaker (they normally say something like ‘I caught around 60% – 70% – 90% percent).

2. Transcription & diagnostics (~25 minutes)

The following several stages are done without the projector – the students won’t need the video, which would only be distracting.

- Students listen to the first part of the extract they’ve just listened to line by line, transcribing it.

- At the end of the stage, the student listen to the part they’ve transcribed again, just to overview what they’ve done and experience understanding the speaker. This ministage takes little time but it’s crucial for the students’ motivation and sense of progress.

The goal of this stage of the lesson is to identify the features of connected speech that make this particular speaker challenging for this particular group (check out this text for a great overview of features of connected speech with examples).

The students listen to each phrase a couple of times (make sure the phrases you’re playing are not too long and so can be held in memory), transcribe them and then share with the teacher what they caught. The teacher writes up their versions on the board and, whenever some common English word poses difficulties because its pronunciation differs from the dictionary form, asks the students to listen again and say how the word sounded in the audio (in my experience, when their attention is directed towards the pronunciation of an individual words, students normally find it easy to hear what sounds are dropped and they readily supply that e.g. ‘that’ was pronounced without the final ‘t’ / ‘was’ was pronounced like ‘wz’, and so on). On a specially designated part of the board, the teacher builds up a list of frequent English words and expressions exhibiting features of connected speech that the students failed to catch, grouping them . Midway through the lesson the board looks something like this:

Variations. At lower levels (B1/B1+) and/or at the beginning of the course, I analyzed the audio before the lesson, identified the most prominent features of connected speech in the speaker’s accent and produced a gapped transcript, gapping out frequent words and expressions that exhibited those features, in order to support the students and direct their attention to these listening difficulties. Even with the support of the text, it took the students around 30 minutes to work through and make sense of features of connected speech in ~20-30 seconds of video.

With B2+ groups and with the weaker groups towards the last third of the course, I’ve started to ask the students to transcribe without any support (and also to ‘transcribe’ orally in pairs, only stopping to write something down when it becomes evident that a particular phrase is unclear for the majority of the students and they need to hear it more than twice to reproduce and to get feedback on what they hear (as opposed to what the speaker is saying). At the moment my groups get through around 2 or 2.5 minutes of video, transcribing them this way.

3. Intensive training with specific words and expressions (working intensively on decoding difficulties) – 20 minutes.

Teacher says that s/he is going to play several phrases with some of the expressions that are difficult to catch. She

- directs the group to one of the words/expressions collected during the previous stage (e.g. ‘was like‘)

- asks the class to remind him/her what the expression should sound like in fast speech (/wzlaɪ’/)

- asks them to listen to just one line and catch just that word/expression (‘listen and catch just /wzlaɪ’/).

- those students who have caught it, should try and catch the words around the expression (do board the task!)

See below for details on how to find and play the bits of the video that contain a specific expression.

Each time, the teacher plays the line two or three times, making sure that everyone in the group has caught the expression. If someone says they haven’t, I normally

- react to that enthusiastically (Cool, that’s the reply I was expecting!) to encourage weaker students to signal their difficulties

- help the students who haven’t caught the expression by, e.g., playing the line again, stopping it right before the word, saying it the way the speaker is going to say it and then playing the word (alternatively, you can play the word in isolation – again, see below for details how to do that

After that, I encourage the stronger students to supply what’s around the expression (sometimes new features of connected speech get identify and immediately make it to the corresponding part of the boards).

In my experience, it takes 5-8 lines for students to start catching the word/expression (when I see that the students won’t need much more practice, I start counting lines down – I’m going to play just 4 more instances of this word; 3 more instances etc so that stronger students don’t get frustrated.

Normally in one lesson we go through three to five problematic words / features of connected speech in this way.

Features of connected speech that frequently come up:

- Disappearing /t/ and /d/ at the end of the word (that -> tha’); this also happens with other plosive consonants, that is /p/, /b/, /k/ (like -> li’)

- Disappearing initial /h/ in words like ‘her’, ‘him’, ‘his’, ‘have’, etc (e.g. ‘makeim pay’)

- ‘Under-pronounced’ functional words (was -> wz; there’s -> thz; used to -> usta; should -> shd; can -> cn)

- Reduced diphthongs, e.g. our, out sound like ‘ar’, ‘ut’; I’ll/I’m sound like ‘ul’, ‘um’.

- Some adverbs get hugely reduced (notably, probably -> probly, actually -> ashly)

- In some accents vowels get replaced, e.g. BrE speakers often pronounce u in pub as oo in books

- If you need to train your learners to understand features of a particular accent, check if there’s a Wikipedia page about that accent (non-Native Speaker accents are also dealt with in Learner English by Michael Swan).

Potential pitfalls:

- I’ve found that if there are more than one words that exhibit the same feature (e.g. ‘her’, ‘him’, ‘his’, ‘have’), it’s still a good idea to first let the students train with the same word (say, her), then with another (him), and only then ask them to catch one of these four.

- Some instances of these words will actually be quite clear and close to dictionary forms. You can prepare by anticipating what words will need to be targeted, listening to the corresponding lines before the lesson and choosing which ones to play; however, I find this a bit counterproductive – after all, if the word is clear, you can just acknowledge that and move on to the next line

4. Listening line by line (working on meaning building) – 20-25 minutes

Hand out transcripts and ask the students to cover them (I hand out colour paper :)). The students practice listening to a sentence or more from the text once and trying to understand the meaning. Stress that their task here is not to transcribe word for word / remember the sentence verbatim but to catch the meaning.

The students listen to the sentence once and, in pairs, discuss what they caught (I usually assign them letters – student A and student B – and ask them to take turns to report what they’ve heard, to encourage weaker students to pull their weight). Through that the students scaffold each other and you get a chance to assess how much they understood.

No feedback is necessary here – after the students have talked about what they caught for 20 seconds or so, tell them that they are about to hear the sentence again. Ask them not to discuss it this time (although in my experience some pairs will) but instead to read the line right after they’ve heard it, underlining everything they didn’t catch.

After that, ask them to play the line again in their head (Prepare to listen to it again and understand it without looking at the text). Before playing one more time, remind the students that you want them to listen without reading.

Repeat the process.

Normally we go through around a page of transcript in this way.

Variations.

- Once the students feel more or less comfortable catching a sentence (probably second, third or third time I try out this task), I tell them that I’m going to gradually increase the length of extract, playing two sentences, then three sentences etc.

- Around the middle of the course, when I start playing really long extracts (3-4 sentences or more, up to half a page of transcript), I encourage the students to visualize everything they hear. This is an issue that comes up quite a lot in research on language acquisition and material development: learners of second languages tend to underuse visualisation when listening in comparison to when they use their first language, falling back on purely verbal processing or even translation, and need training and encouragement to visualize (see, e.g. Chapter 1, Materials Evaluation by Brian Tomlinson in Developing Materials for Language Learning). Stories told in interviews are usually quite visual and lend themselves well to that task. Before instructing the students to visualize, I warm them up by asking them to imagine a rose and asking them what it looks like and where it is; then asking them to add a cat to the picture and share visual details of the picture with their partner; then eliciting a few more objects from the group, each time asking the students to add these objects to their mental ‘pictures’ and sharing with their partner. When we do the ‘visualized’ version of the listening task, I ask the students to not merely report what they’ve caught to their partner, but also report the visual details too (e.g. if the speaker mentions an interview they did, I encourage them to ask/share what the room was like, what the interviewee was wearing, etc).

Potential pitfalls.

If the listening material is too difficult for the level, this task might get quite frustrating (e.g., pre-intermediate learners are likely to get challenged by this procedure), but most interviews are OK for B1+. Films in an unfamiliar accent, on the other hand, might be quite challenging even for a B2+/C1 group.

5. Watching same extract again + listening to another extract (evaluating progress) – 10 minutes

This stage is pretty straightforward: the teacher switches the projector on, the students watch the entire extract again – having worked with it, they will understand more or less every word. After that, I let them watch another bit of the interview (and share in pairs what they caught) – to let them evaluate their progress.

6. Reviewing what has been done & setting the homework – 5 minutes.

Ask the students to mentally go through what features of connected speech they’d focused on in the lesson; encourage them to remember specific examples; having thought for a minute, the students share in pairs.

Set the homework. I normally ask the students to do more of everything we did in class:

- Listen to more instances of problematic words

- Go through another part of transcript ‘line by line’ (the students could do that with the listening extract they did at the previous stage)

- Watch the remainder of the interview

- I encourage the students to alternate between ‘close’ listening (stopping after every few sentences and reviewing the transcript) and listening for pleasure.

Why unabridged interviews?

As I mentioned above, I mainly structure the lesson around an unabridged interview.

The reason I use unabridged materials (as opposed to coursebook listening) is, firstly, that they are closer to the kind of listening the students will have to do outside class. My own (rather unusual) experience of learning the language highlighted the need to use authentic listening in class all too well: by the time I’d reached C2 level I’d never been to an English speaking country and I’d watched no more than 10 or so films in English. All my exposure to spoken English was either in class, talking with non-native speakers or through numerous coursebook audios and audiobooks. So, it was after I passed a C2 level exam (CPE) that I started watching films in English and realized that I couldn’t understand much. My in company students report a similar problem: they have no trouble understanding coursebook audios even in advanced coursebooks, and yet they complain that talking with English speaking customers on skype in the first month of a new project is very challenging.

The reasons I use interviews and not, say, films or trailers are

- The feeling of progress. The fact that there is only one speaker means that the features of accent that the students need to get used to are consistent and, in my experience, ninety minutes are enough to get used to and feel progress understanding even the most challenging speakers. I’ve tried working with films and series, but somehow it invariably felt a lot less satisfying.

- Interviews are inherently chunked into 3-5 minute extracts (in contrast to, say, TED lectures), so there’s a nice feeling that we’ve watched something complete.

- Interviews that I use mostly last around an hour, which means that, first, there are usually plenty of instances of problematic words and expressions (e.g. if it turns out that the students don’t catch something like ‘there’s’ or ‘used to’, chances are that this expression will be reused a few times); secondly, this means that the students who want to continue working on this accent have plenty of material to work with at home. I must say that those students who did work with videos at home have showed remarkable progress over the course of three months – and it not only shows in their greatly improved listening skills, but is also evident in their overall better command of English).

As follows from the procedure outlined above, you’ll need to somehow rapidly locate and play those parts of the video that contain a specific word. I use two tools to do that: one is built into youtube and another Aegisub, a subtitle editor.

Youtube. I work with youtube.com videos that have closed captions (automatic captions are no good, but some channels have human-produced transcripts – see the links). If a youtube video has closed captions, you can look through the whole transcript, position the video on any line (so, you can easily replay any line any number of times). Also, you can search for a specific word or expressions in the transcript (and play just those lines that contain that word/expression), which makes youtube an ideal tool to give the students practice in catching some common English words.

Here are a few screen shots showing how to use transcripts on youtube.

1. To open the transcript, click on ‘More’ under the video, then click on ‘Transcript’:

2. Check that the subtitles were produced by a human transcriber: automatic captions contain too many mistakes, so they’re impossible to work with .

3. Use search built-in in your browser (normally, Ctrl + F) to search in the transcript; click on the line that contains the word to position the video on that line.

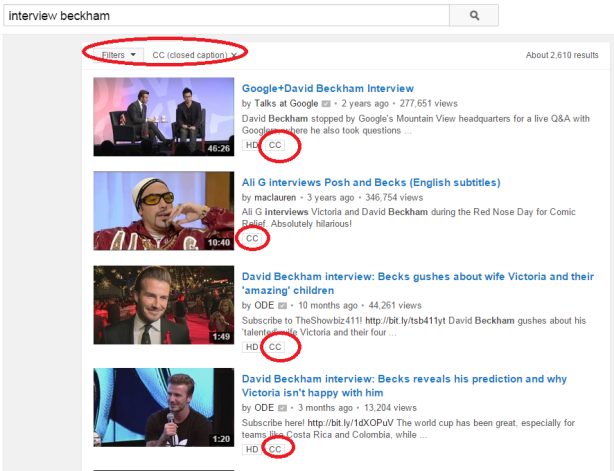

4. In order to find videos with captions on youtube, you can use a filter:

Those videos that have captions are tagged ‘CC’:

Pluses of youtube: no need to download anything before the lesson; no need to worry about copyright: if the video has standard youtube licence, you can play it in class;

Pluses of youtube: no need to download anything before the lesson; no need to worry about copyright: if the video has standard youtube licence, you can play it in class;

Minuses of youtube: you can only play the whole line of text, so if the students are having trouble catching just one words, you can’t play that word in isolation; also, obviously, if you’ve got bad internet connection, you’ll have trouble playing the video in class; finally, only a very limited number of youtube videos have transcripts; ads that it displays can be a bit inappropriate.

Aegisub

As an alternative to using an online video, you can work in the same way with a video stored on your computer using Aegisub subtitle editor. You can use it with any video you’ve got subtitles for (e.g. a film), but I normally download interviews and subtitles from youtube, using these two services: http://keepvid.com/ and http://keepsubs.com/ (first time you use them, the site might ask you to install Java). Check out this video tutorial if you’re having trouble downloading the videos.

Again, you can probably easily find a tutorial for working with Aegisub on youtube, but here are the essentials:

1. Open the subtitle (.srt) file with Aegisub. After that, open the corresponding video file:

2. Once you’ve loaded the video, just like with youtube, you can position the video on any line by double-clicking that line, and then play the video from that point:

The black-and-blue strip on the right allows you to select and play any bit of the file. I use it when the students are failing to catch a word or two, to play that word in isolation.

3. Like with youtube, you can search through the transcript to locate samples of words/expressions your students have failed to catch. Even more, you can use so-called ‘regular expressions’, which allow you to look for more than one expression at once.

| means ‘or’

* means ‘repeat this many times

E.g.

- if you type in there(‘s| is| are) you’ll find all instances of there’s, there is and there are (because you are looking for there followed by ‘s or is or are);

- if you type in (What|When|How|Why|Who) (do|does) (you|I|he|she|it), you’ll find a variety of questions in present simple, e.g. ‘How do you..’ or ‘Why does she’…; (because you’re looking by one of the question words followed by do or does, followed by one of the pronouns)

- if you type in (What|When|How|Why|Who) ( are|’re| is| ‘s| am|’m) [a-z]*ing, you’ll find questions in present continuous, because you’re looking for one of the question words followed by a form of ‘to be’ followed by a combination of letters ([a-z]* means ‘any number of letters in the range from a-z) that ends in ing.If you want to use this feature and need more help, look through the Basic Concepts section of the Wikipedia article on regular expressions.

Links. I’ve found quite a few youtube channels that have accurate subtitles. There a videos in a variety of genres, accents and lengths. Check out this post – it will be updated as I find more good links.

What’s next in the series?

Next I will post actual materials and lesson plans I’ve used during the course (Update: the lesson on an Australian accent is already available). If you follow the generic plan outlined above, you basically can teach a lesson using any interview and you don’t really need to develop any materials. I’ll still write my lesson plans up, though – first because locating videos that are ‘interesting’ accent-wise and thus suitable for stronger students is quite challenging (I sometimes go through a couple dozen before I land on one that seems suitable); secondly, because I’ve read the transcripts and located interesting stories in those materials; and thirdly because reading through those lesson plans will probably give people who read them a good idea of what features of connected speech tend to come up a lot – and hence are worth looking out for.

Hi there – Really enjoying reading your blog! There are a lot of crap tefl blogs about so it’s refreshing to read something that comes across as equally principled and enquiring. I’ve just come back to the Field book a couple of years after my (intensive) DELTA course and discovered it much more inspiring now I have the luxury of time to digest it. I’m currently trying to work on alternative approaches to listening in my Elementary and Advanced gen english classes, mostly in the form of shorter remedial sections but will definitely have a go at your lesson shape with my adv students, whose demands sound quite similar to the students on your listening course. Interested to hear more about your experiments – Thanks for the material.

PS I’ve found a good source (but unfortunately not subtitled) of regional UK accents in natural conversation in short sections is here at the listening project at the British library… challenging but searchable by topic and involving interesting topics… http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/features/the-listening-project

Hi! Thanks a lot for stopping by – it’s so nice to hear from someone who reads this blog! And special thanks for the link you shared! I’ve checked it out and the videos are just great (I’m a big fan of storycorps, and it’s good to know that there’s a similar project in British English).

Could you share how you approach giving remedial listening practice? I feel that I’m slacking a bit when it comes to targeting listening skills in general courses – I’ve been doing ‘something’ but I definitely still need to develop a (way more) principled approach. So it would be very interesting to find out what other people who are trying to take Field’s advice on board do..

Olya

With my Elementary sts they did terribly in their last listening test and I realised it was partly down to difficulties hearing the -ed inflection in the stream of speech (that term had been the Ele 2 New English File past tense assault and I realised I hadn’t given them enough listening support). This term I’ve been doing regular 15-30 minute sessions at the start of class incorporating language from the last 3 terms in the form of either short phrases or a short text. There are one or two listenings form the textbook I’ve recycled or I’ve had other teachers record them to give variety of voice type and allow me to replay them consistently. I’ve tried to avoid looking explicitly at a particular structure we’ve focused on in the same lesson so as to avoid it turning into a dictogloss, so I leave a lag of a lesson or two for new language, and have also tried things out ahead of a new language point. It’s a work in progress but each time has been a variation on transcribing individually then working in pairs/groups to reconstruct on mini whiteboards, noting down all possibilities. We listen to the phrases that cause problems multiple times with sts discussing further, then we refer to the written form on the IWB and sts circle areas of difficulty on their whiteboards. We do further listening to identify why, asking them to think how the phrases sound and mouthing or repeating them. Each time it’s been a nice springboard for focus on particular features of connected speech causing them issues and, as they’re Elementary, it doubles as an introduction to basic features basic features of connected speech in a more formal way. I generally then knock up a quick dictation activity on the spot to give further practice of one or two problems, foisted directly from Field. For example, contrasting similar phrases for rhythm and linking sounds (e.g. There’s a toy in the bathroom/there’s a toilet in the bathroom), identifying if a phrase refers to the past or present, identifying all instances of the schwa/weak forms/function words etc in the remainder of the text, and also common chunks (What are you.. /wɒdəjə/) have been really useful for them. They’ve been really receptive to this approach and on one occassion we got so involved we ended up doing the best part of a 90 min lesson on things that came out of it. It’s been quite organic and I’m somewhat restricted by the format of our courses here but i’ve been a great learning experience so far. Next i’m going to try the Hamilton method you documented, noting down only the stressed syllable sounds now they’re more confident…. and I hope you don’t mind but I’m going to filch your listening lesson shape for an observation coming up with my Adv class next week!

This is an awesome blog post!

Thank you Jamie! Started reading your blog, really enjoying it too. 🙂