Two days ago I attempted to teach my Elementary Business English students to produce extended monologues listing advantages and disadvantages, using linking devices that are considered to be ‘B1’ or even higher in typical Speaking exam marking criteria.

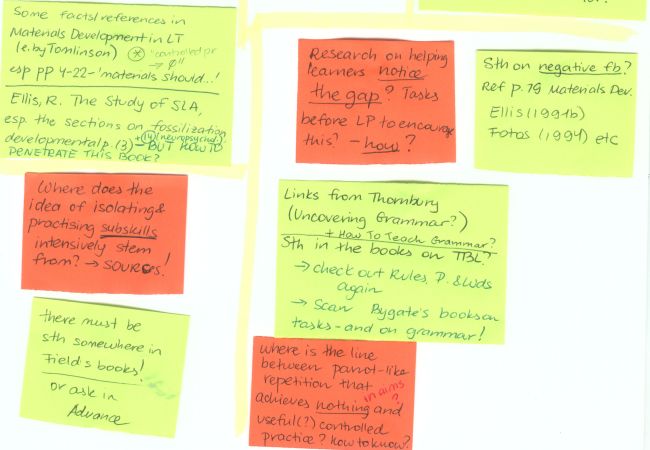

This is my first attempt to write a lesson from scratch at this level and it would be great if someone had a look at this – any suggestions/criticism is highly welcome. It worked well with my group, but that group was quite small and I was able to address any problems straight away, so I’m not sure what pitfalls I might still be overlooking. Also, there are some ‘nagging questions’ at the end of this post concerning adapting the course to an individual company setting – I hope to hear what other people think.

Level: elementary (my students are more like ‘low elementary’ although, as they read technical documentation, their vocabulary, especially passive vocabulary, is better than their control of grammar and their skills.)

Context: Business English (in-company, an IT company)

Time: 90 minutes

Materials: worksheet.docs or worksheet.pdf; it’s nice, although not essential, to have a projector connected to a laptop for the text analysis task (stage G)

Procedure: the essential stages are stages E, F, I, J, K and M, in which the students familiarize themselves with the model, look for the target language in the text, organize it, practice using it under fully controlled conditions, revise it again and then use it to produce their own monologues. Stages B, C and D pre-teach vocabulary. Stages G, H and L focus on accuracy.

A Which opinion do you agree with?

Procedure: just ‘a show of hands’?

I prefer working from home.

I prefer working in the office.

B Some of these sentences are about working from home and some are about working in the office. Fill the gaps.

Procedure: in a mixed ability group, allow weaker students to look at C straight away; stronger students should cover the verbs

- When you work from home, you _________ all the time, even at night.

- You _________ in social and professional isolation.

- You _________ money on transport.

- You _________ less time commuting.

- When something _________ wrong, you can’t ask other people to help.

- You _________ more time for your family.

- If your computer _________ down, your company doesn’t give you a new one.

- You _________ learn from your team.

- You can _________ what to do.

- Offices _________ extremely noisy and I just can’t _________ there.

- My family _________ that I’m working and _________ me all the time.

C Did you use some of these verbs?

work

are x2

concentrate

distract

decide

break

have

go

can’t

save

spend

not understand

D Look at the sentences from B again. What happens when you work from home? What happens when you work in the office? Sort them.

E Does Olya prefer working from home or working in the office?

How many pluses of working from home does she give? How many minuses? Underline them.

I’m a teacher I prefer teaching face-to-face for three reasons.

I’m a teacher I prefer teaching face-to-face for three reasons.

First of all, I work better in the company of other people. Another upside, for me, is that I actually enjoy going to and from work because I come up with a lot of ideas on my way to work. Besides, I don’t really enjoy giving lessons online because it’s very difficult to share materials on the Internet.

Of course, working ‘offline’ has its disadvantages. The main minus is that getting to and from work takes a lot of time. Also, I have to carry lots of books around.

But as I said, I think that the pluses outweigh the minuses.

F Which of these words can you see in the text? Underline them. Some of them mean ‘plus’ and some of them mean ‘minus’. Sort them:

| upside downside advantage disadvantage |

Plus: _______________, _______________

Minus: _______________, _______________

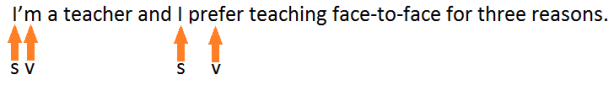

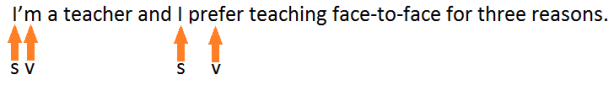

G English sentences have a subject and a verb.

For example:

Find subjects and verbs in the text.

Then complete the rule:

When we use a verbs as a subject, we use verb+ing /the dictionary form of the verb

Example from the text #1: ________________________________

Example from the text #2: ________________________________

After prefer and enjoy, we use verb+ing/the dictionary form of the verb

Example from the text #1: ________________________________

Example from the text #2: ________________________________ |

Procedure: during the feedback stage, I projected the text and highlighted the subjects and verbs. The result looked like this:

Also, this table was added to the document shared via dropbox where I write up everything we study with this group, and part of the homework was to repeat this task at home.

H Find mistakes in these sentences.

- I think that working from home it’s more efficient.

- For me, the main disadvantage of travelling abroad you don’t know the language.

- First of all, go to and from work takes time. Besides, it’s expensive.

- Another plus, I like talking with my team.

- Another plus – is that I feel more comfortable at home because it less noisy than the office.

- I enjoy work with other people because we share our ideas.

Procedure: again, I used a word document during the feedback stage and the students will be repeating this task at home.

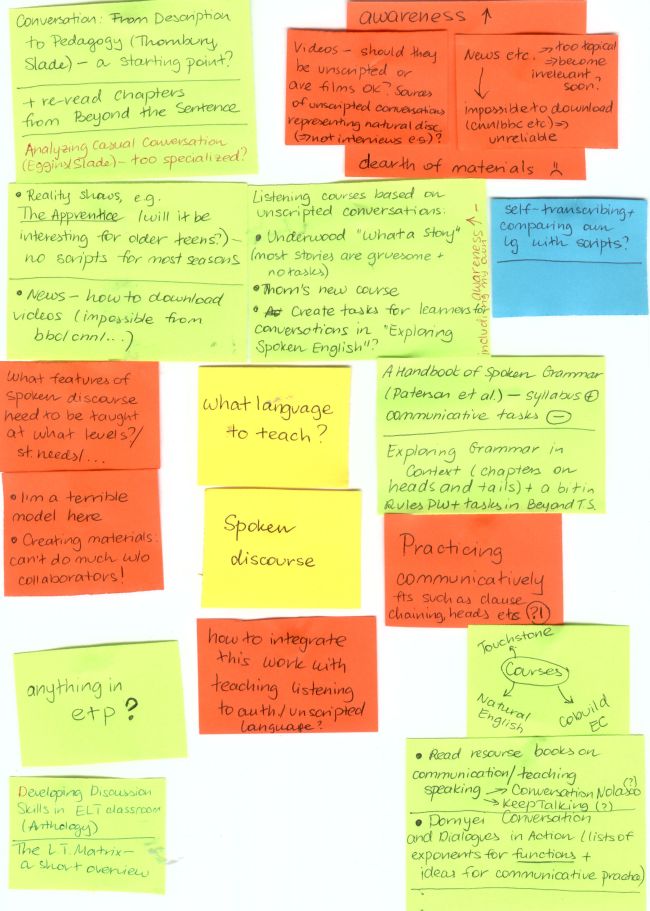

I What expressions in the text make it logical? Find them and put them on this mind map:

Procedure: students should come up with this; model on the second paragraph first; after the students have finished, elicit the map, board it and model pronunciation.

J Look at the mind map and retell the text.

Procedure: first model with a stronger student, then pair the students up.

K Write the expressions again from memory:

Procedure: allow the students who are stuck to look the expressions up again in the text (not in their mind maps).

Procedure: allow the students who are stuck to look the expressions up again in the text (not in their mind maps).

L Find mistakes in these sentences.

a. I think the pluses of working from home outweight the minuses.

b. At first, working with new technologies is more risky. Also, it’s a lot more difficult.

c. I think that working from home is better than working in the office from the following reasons.

M Over to you: do you prefer working in the office or working from home? Plan your monologue. Tell the class.

Procedure: I did this as a whole class activity but my group is quite small.

_________________________________________________________

Reflection. This lesson was quite different from the lessons I’d had before with this group. There was a lot more language analysis and a lot less ‘talking’ (even the monologues at the end didn’t serve any communicative purpose, really!) However, after they produced their own monologues at the end (they used both the reasons given in exercises B and their own reasons), I told the students that, apart from their speech speed, they sounded intermediate – and I meant it. I do think that this experience of talking at length will be quite motivating for them.

I think this was the first time I showed the students complex sentences (although we did a short focus on relative clauses in the previous lesson). Analyzing that text to find subjects and verbs had possibly been the most cognitively challenging task in that course so far. I think that this task might have contributed to their appreciation of English sentence structure (Russian doesn’t have catenative ‘be’ and they still drop it a lot when left to their own devices).

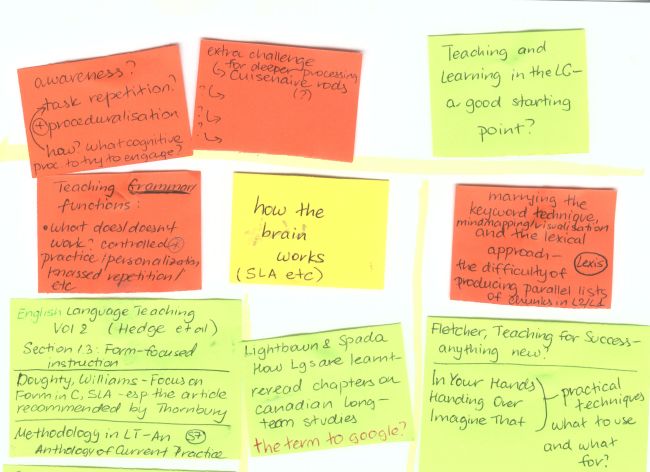

The motivation behind teaching this sort of monologue came from my own experience as a language learner. I wrote about this already in this post (scroll down to the wordle if you’d like to have a look), but basically what happened was I just tried to speak to my teacher in German, switching to English whenever I was lacking an expression and she wrote the German equivalents of the expressions I needed in a shared file. A while ago I analyzed the language that came up during my first ever attempt to have a proper conversation in German (my receptive skills were around B1 at that point) and I noticed that some types of language featured prominently: there were a lot of sentence adverbs (unfortunately/ luckily/mostly / also / at least) and language for evaluation (it was ok/worst of all was that../it was terrible/ it was challenging). So now I want to come up with ways to teach such language as early as possible in the course to enable the student to string basic vocabulary into complex ideas.

The questions I’ll have to think about:

- Would this procedure work with a bigger group where I wouldn’t be able to provide as much on-the-spot correction?

- Should I have chosen a different set of linking expressions here, e.g. should I have picked a longer but more versatile ‘another reason why I prefer sth’ instead of ‘another upside’?

- What other ‘frameworks’/speaking subskills to teach/prioritize? How to choose the potential mistakes to focus on? (the ones I used in stage H came from another group’s writing on a similar topic) How to predict what language needs to be pre-taught, especially in a Business English course targeted to a specific line of business? (right now I simply assign a task to a higher level group working in the same company, note down what language comes up, then feed that language to the ‘starters’)

- Should I actually ask my students to brainstorm reasons between classes in Russian and then preteach that vocabulary? If yes, how to scaffold that – I tried once, they just ignored the task.

- Am I re-inventing the wheel here? It took lots of time to come up with this material – doest the fact that I need to write that myself mean that I am misusing BE coursebooks?

- My students need to take part meetings reporting on their progress, stoppers and future plans, write emails along the same lines etc for work. Should we really be discussing the relative benefits and disadvantages of working from home?

- If not, how do I manage to produce materials without spending 5 hours preparing for each individual lesson, if they need that much scaffolding and language input?

Ideas?

Probably, to be continued. 🙂