Another one in a series of fluency-related posts – more links here: contents.

One of the most widely known classroom activities that target fluency is Paul Nation’s 4-3-2 technique: students tell the same story (or do the same task) under progressively stricter time constraints. The idea is that students are pushed to perform faster and are forced to restructure the ‘routines’ they use, and so the ‘formulation’ phase of speech production speeds up.

With my B1-C2 level students I use a slightly more complex procedure. Students find interesting articles online in order to share them in class, but instead of just reading and retelling them them to their classmates using more or less what linguistic resources they currently have, they actively mine text for collocations. This tweak to the activity seems to tie in nicely with a lot of insight into fluency described in the previous post. A variation of this technique which I think really does help to teach functional language at lower levels/to students preparing for exams such as IELTS is described here.

The full version involves some homework on the part of the students and takes around 80/90 minutes of classroom time, although there are some shorter alternatives that do not require homework.

Homework stage:

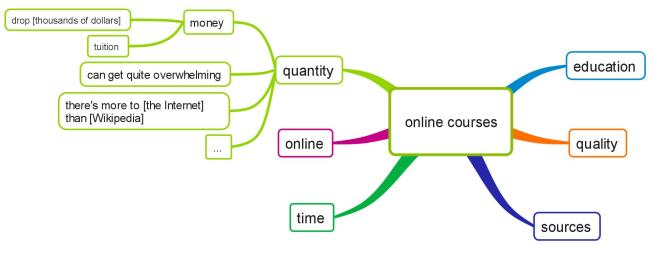

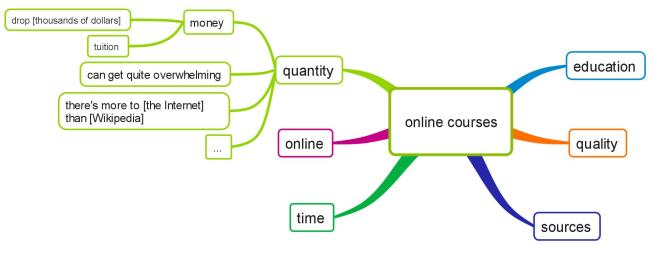

- Students choose an article on the internet

- They mine the text for sets of related expressions (big thanks for this technique to Mark Rooney and Ewan Dinwiddie, in whose Delta Module 2 lessons I first saw it) and organize these expressions into a mindmap. For example, in this online article on education, one predictably finds lots of expressions connected to studying (e.g. ‘grant you a college degree’, ‘take a year-long course’ and ‘broaden your knowledge’) and the internet (e.g. ‘without ever leaving your computer’, ‘bring free education to the masses via the internet’ and ‘available under open licences’), but on closer look lots of other related sets emerge, e.g. ‘quality’ (‘top-notch education’, ‘featured courses’, ‘which few you might want to steer clear of’), ‘quantity (‘it can get quite overwhelming’, ‘over 22 universities in the US alone’, ‘courses on tons of subjects’) and so on.

Classroom stage:

- Students attempt to recreate their mindmap from memory (~10 minutes) and then look through their original mindmap and, ideally, through the text to see what’s missing (~5 minutes) – they won’t remember more than 30-40% at this stage, but this ‘test’ stage primes them to benefit more fully from revising the map

- Students practice pronouncing expressions from their mindmaps as fast and fluently as they possibly can (this can be tied in with work on connected speech, e.g. they could be asked to look for instances of linking/weak forms and practice pronouncing those)/resolve any queries regarding pronunciation with the teacher’s help (3-5 mins); I also share this resource that automatically transcribes lists of expressions, so that students can check pronunciation at home

- In pairs, they retell their article to a partner trying to use the expressions from their mindmaps – there’s always some discussion going on, but this is primarily a monologue (6.5 minutes/each monologue for average-length articles)

- They look at their mindmaps to see what they forgot to mention/what expressions they didn’t use and why (5 minutes)

- In new pairs, they retell their article (5.5 minutes/monologue)

- Having briefly looked at their mindmaps again, in new pairs they retell their articles in 4.5 minutes

For this activity students are normally seated in two circles facing each other (so at each stage those sitting in the inner circle move to the next partner). By the end of the activity those students who sit in the same circle haven’t heard each other’s stories, so they can pair up with someone from the other circle and share what they’ve heard/what they liked the most or found the most surprising (this normally takes another 10 minutes or so).

Here are a few mindmaps produced by my students. What I’ve been noticing is that over time students start producing much better quality maps in terms of expressions they notice.

In my experience, for the activity to be a success, the following factors/steps are quite essential:

- [a shorter version] start with shorter texts or integrate this with jigsaw reading (lists of places to go to/things to do/films to see etc lend themselves to this, e.g. in a recent class, my B1 students read one tip each from 10 Things to Do in New York City, shared these tips mindmapping between changing the partners and in the end decided which of those they’d like to do the most).

- [introducing the activity: a lesson plan] try the whole procedure out in class, training the students in sub-steps: first introduce the idea that texts contain sets of related expressions and give them practice in identifying these; then give them practice creating mindmaps; then run the whole activity (mining the text for expressions + minmapping + recreating the mindmap + retelling the text) on the same text together – I’ve used coursebooks texts and also the first two paragraphs in this text, which was more than enough material for a ninety-minute class of B2 students.

I usually try to first draw the group’s attention to the fact that they don’t remember the expressions from the text; to do that, I ask them to close the text and shout out words and expressions that were there; I board their suggestions and then I ask them what sets of related expressions they see – this helps to introduce the idea of lexical sets and a mind mapping; I draw the draft mindmap and ask students to copy it and to complete it with more expressions from the text. Here’s the draft mindmap we created for the text on education linked to in the previous paragraph:

After that, the students finished their mindmaps – an average one looked something like that:

Having done that, they recreated them and retold the text to each other, I then split them into groups: these groups read different paragraphs from the text, repeated the cycle of mining for vocabulary/mindmapping/recreating the mindmap etc helping each other, and then they retold these paragraphs to people from another group

- [collocations – NOT unknown vocabulary] This activity works great with collocations, but only as long as they don’t contain completely unknown words. If they do, I’d suggest using the keyword technique to learn them first.

- [safety net] I haven’t needed this yet because my students normally do find and read the articles, but probably it’s a good idea to keep a few interesting print-outs to hand. In that case students who come unprepared can read an article to share while those who did prepare are reproducing their maps; I also ask my students to share the links to the articles they’ve found, as well as photos oftheir maps, in a dedicated thread on a class blog – so I know whether they’ve prepared or not

- [making the activity methodologically meaningful for students] It’s important to let the student know the rationale behind the activity and explain that they need to speak faster and faster – otherwise they will just skip some parts

- model the activity: tell the students a story based on an article, encourage them to ask questions/interact with me/clarify unknown vocabulary; share sources (e.g. http://www.economist.com/science-technology, www.theguardian.com/, http://www.newyorker.com/ for longer articles and lifehacker.com, http://www.quickanddirtytips.com/ and http://coolamazingstuff.com/ for shorter/more fun articles and lists)

- [personal experience] it was very important for me to try out the entire activity on my own first, so that I knew of the likely difficulties and was able to reassure those students who thought it was impossible to recreate the maps; it is impossible to remember more than 30-40% on the first try, but after a couple of retellings it becomes pretty easy. What I did was pretty extreme, as I tried the activity with a 3-page article from New Yorker on a ramble through the city, and although there was no real plot in the article and although there were over 60 collocations on my map, third time I tried I could retell it using a significant proportion of collocations

- [catering for tastes] some students don’t like mind-mapping – it’s ok to be flexible, as expressions can be organized into short lists, for instance

- [revision] encourage the students to revise their mindmaps for a few days and store them safely/upload them to a group blog

Some of the articles my students have brought to class (might be useful to get the process started):

3D printers get cheaper, faster – and more mainstream

Apple iPod creator launches intelligent smoke alarm

Dark energy A problem of cosmic proportions

‘My iPad has Netflix, Spotify, Twitter – everything’: why tablets are killing PCs

Why Do Our Best Ideas Come to Us in the Shower?

Brain-to-brain communication is not a conversation killer

Shodan: The scariest search engine on the Internet

Male brain versus female brain: How do they differ?

A few words on why I think this activity makes sense in view of fluency research

In my previous post I wrote a lengthy overview of what factors are known to influence fluency and how these are mapped to the stages an utterance undergoes before being said. To sum it up very briefly, one needs to

- conceptualize/macro-plan: come up with what to say and how to structure it

- formulate: micro-plan the utterance, retrieve vocabulary in chunks (as opposed to individual words), automatize grammatical processing

- pronounce chunks fluently

- monitor after saying the utterance

A regular 4-3-2 activity supplemented with mind-mapping

- promotes out-of-class reading and gives the students practice in discussing some general interest stories, which might conceivably help with coming up what to say

- encourages students to notice vocabulary in texts, write it down, and test themselves, and provides students with a cognitively engaging exercise of identifying lexical sets present in the text (I personally don’t feel bored after a whole hour of doing that), all of which improves retention; promotes learning vocabulary in chunks, which leads to fluency gains

- helps students to automatize grammatical processing through pushing them to perform faster and faster

- encourages them to pronounce chunks naturally through the pronunciation practice stage, which improves perceived fluency

In the next post I describe how I use this activity with lower levels to help them with functional language used in social encounters.

A few interesting references

To Really Learn, Quit Studying and Take a Test – on the effect recalling and subsequently re-reading a text has on retention

Nation, P. Learning Vocabulary in Lexical Sets: Dangers and Guidelines – Learning vocabulary in lexical sets (e.g. ‘apple, pear, plum’) is counter-productive, learning thematically related words (e.g. ‘frog, pond, green, slimy, hop, croak’) produces the best results.