This is one more post in my series of posts about the EVO 2017 session on teaching listening. In this post I want to summarize one more issue that was raised during the session: the use of authentic materials with lower levels.

Below you’ll find some of the ideas and experiences that the teachers participating in the session shared:

- Watching short clips for fun

- Using songs

- Grading the task by using the material as a warmer or a lead in

- Micro listening: focus on grammar

- Vox pop videos for word hunt or micro listening

- Watching the video without the sound

- Some thoughts on the role of assessment and a case study: following a news story

- Authentic listening (and speaking) out of class

But first, let’s look at some pros and cons of using authentic materials with lower levels.

A lot of the session participants voiced concerns about using authentic materials with lower level learners, such as:

- it takes a lot of time to find extracts that lower level learners would have any chance of coping with;

- even with these extracts, the learners are often frustrated that they don’t understand much;

- one often hears ‘grade the task not the text’. But what are some examples of graded tasks? And won’t it happen that we’ve graded the task, but the learners fail their ‘inner task’ of understanding more or less everything, and still feel frustrated?

So do lower level learners need to work with authentic materials at all? Here are some reasons why they do:

- the learners might be exposed to authentic materials outside class (especially in ESL / business Engish settings, but also on the Internet and while they travel) – they need to prepare for that in the safe classroom environment;

- coping in some way with authentic materials gives tremendous sense of achievement to lower level students

- using authentic materials in class will give the learners the courage to try to ‘get out there’ and start practicing out of class, which is great for language acquisition. This will be especially useful if we discuss with the learners specific ideas where they might find suitable materials and what they could do with them.

Image source: flickr.com/photos/wolfgangkihnle/6050220330

So what are some sources of lower level materials, and how can we use them in class?

1. Watching short clips for fun

Oksana Kirsanova, an English teacher from Russia, encourages her learners simply to watch very simple funny videos like the one below.

The video could be shown in class or shared with the learners to watch at home. The learners watch for enjoyment – Oksana sets no task. If the video contains a lot of dialogue, she finds a version with Russian subs.

This is a very simple way to introduce the learners to authentic materials. You probably know a lot of good videos already (who hasn’t shown Eleven of We’re sinking at some point in class?) but it’s worth building a bigger collection and showing/sharing the videos regularly throughout the course. One good source of such videos is funny commercials. There are lots of compilations on YouTube – if only some commercials in a compilation are appropriate, use TubeChop.com to isolate and share only those bits you want to share (here’s an example of a clips isolated with TubeChop).

2. Using songs

This can be extremely motivating for learners, especially teens (but not only)! There are lots of songs that are suitable for lower levels because the pronunciation is very clear. Again, it’s worth building up a collection to use throughout the course (or Google some ready-made collections, like this one). There are two challenges: doable tasks and finding songs that are relevant for the learners.

Some ideas for tasks:

Svetlana Bogolepova (Russia) got her learners to listen to Yesterday by Beatles and clap every time they heard the word ‘yesterday’ – which is a very simple activity that encourages the learners to notice the words they know in songs. I think this kind of activity could be a great lead-in (or warmer / filler) to some topics dealt with at Elementary level (e.g. adverbs of time or past simple).

We got more examples of tasks to be used with songs from this article by Nik Peachey on A framework on planning a listening skills lesson (scroll to ‘Applying the framework to a song’). Some of the tasks that Nik offers are:

- listening to the song and deciding if it’s happy or sad;

- listening and ordering jumbled up lyrics;

- listening and correcting mistakes in a summary of the song pre-written by a teacher.

Regarding the question of finding relevant songs, I’d predict this would be a real issue with teens, who might not be very motivated by having to listen to, say, Abba! I think the best idea with learners who feel strongly about this is to involve them in creating/maintaining a list of songs with clear pronunciation. The learners could be encouraged to maintain a Padlet.com board like this one curated by Teaching English – British Council.

3. Grading the task by using the material as a warmer or a lead in

One of the concerns that the participants of the EVO raised was that the learners are bound to understand little in authentic materials, which will frustrate them. One way to help learners feel more OK with the fact that they don’t understand everything is to use the material not as the main listening text in the lesson, but as a warmer, setting a task that the learners could cope with.

E.g. with the following video the learners could

- watch the video and guess the topic of the lesson (food)

- watch the video and note down all foods they could see

- a word hunt activity: watch the video and note down all food-related vocabulary they heard someone say

4. Micro listening: focus on grammar

This is something I love doing with my lower level students: using video compilations that show lots of examples of just one grammar point, like this one:

I normally do this as a part of a grammar lesson, asking the learners to fill the gaps the transcript:

1. Spider-Man ________ hero.

2. ______ ready? ______ born ready.

3. A hundred years ago, ______ one and a half billion people on Earth.

4. Exactly! ______ a worker, but now _______ war hero!

5. Oh, right! _______ my sister.

6. But ______ young and proud!

You’ll find the end of this exercise and a lot more links to such videos in this blog post.

A big issue is that these videos come with hard-coded subs. I dealt with this simply by dragging some kind of window, e.g. an open notepad document, over the subs area.

Another issue that one session participant raised was that these extracts are decontextualized. I think that that’s not much of a problem, because the visual element is so rich it provides micro context – notice how the feeling that one gets watching these videos is very different from if you were listening to the extracts.

5. Vox pop videos for word hunt or micro listening

Another source of videos that are ideal for word hunt or micro listening, because they naturally provide multiple examples of the same language feature, are so called vox pop videos (videos in which people in the street get asked the same question – normally there are two or three questions per video).

I’ve found several sources of such videos:

- Speakout video podcasts for all levels, including Starter and Elementary, freely available on their site. For example, the learners could watch the following video and note down all family vocabulary they can hear (word hunt) or count the number of times the word ‘my’ is used (this could lead to a micro ‘pronunciation for listeners’ activity, as ‘my’ is often pronounced as ‘mu’):

- Real English videos uses the same idea. E.g. in this video people in the streets say how old they are – the learners could listen and note down the numbers they hear

- Vox Pop International, an authentic YouTube channel, also contains some videos suitable for lower levels. E.g. watching this video the learners could note down all adverbs of frequency they hear:

- If you are subscribed to onestopenglish, they recently created Live from London, a great collection of such videos with worksheets and transcripts. Here’s a sample video, with ideas how it can be used with Pre-Intermediate learners and higher.

If you want to try how listening to such videos feels, why not try this video in Mandarin Chinese shared by Curt Ford, another EVO participant:

What I like about vox pop videos is that they’re so adaptable to a range of activities: while they could easily be used for a quick micro-listening activity or a ‘word hunt’ warmer as described above, they could also be used in the traditional gist – details – follow-up lesson shape:

- Stage 1: the teacher board the two or three questions asked in the video on the board, uses tubechop to play the corresponding two or three extracts in which people answer the questions, the learners watch and match the extracts to the questions (Variation for a higher level group: the learners watch and guess the questions).

- Stage 2: the learners do a micro-listening (fill in gaps focusing on one grammar feature) or a word hunt activity.

- Stage 3: the questions are used for a speaking activity (either in pairs or mingling).

6. Watching the video without the sound

Heather McKay shared an activity that helps the learners to draw on the paralinguistic features in the clip (body language, context, facial expressions, etc). Before watching the clip with the sound, she plays it several times without the sound, for the learners to draft the dialogue/share their predictions with each other.

Here’s a sample clip she has used this approach with:

A useful source of such clips is Claudio Azevedo’s web sites/blogs: http://moviesegmentstoassessgrammargoals.blogspot.com/

7. Some thoughts on the role of assessment and a case study: following a news story

Two session participants, Tanja Debevc and Keith Murdiff, reported on their experience of what happens when authentic materials become part of the end-of-course exam. They have experienced a real positive backwash, as both the teachers and the learners want to target the type of material that the learners will be assessed with. A big challenge is, of course, designing graded exam tasks that the learners would cope with. Tanja shared a link to a book which features exam tasks for lower levels based on authentic materials.

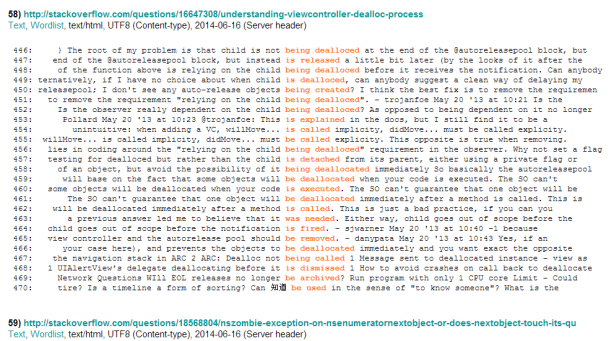

What is more, their experience shows that the learners cope with a lot more than we assume they might cope with. In particular, Keith prepares his learners for an exam in which they need to follow a news story. This is why one of the tasks he sets to his learners is to choose a news story and listen to all news they can find related to the story (online and on the radio) over a period of time. Keith’s experience is that the learners have a lot of context (as he puts it, context is king), the learners are able to cope with, benefit from and enjoy difficult listening texts and discern a lot of detail. The learners are provided with a worksheet that focuses on story-key vocabulary, main actors and their role in the story, predictions on how the story will develop and a summary of the news. The learners use this framework to follow up on their listening in class, sharing with other class members.

8. Authentic listening (and speaking) out of class

I think that the idea for getting the learners to follow a news story outlined above exemplifies two key ingredients for encouraging listening to authentic materials out or class: the learners need specific ideas what to listen/watch and they need very specific tasks to do while they listen.

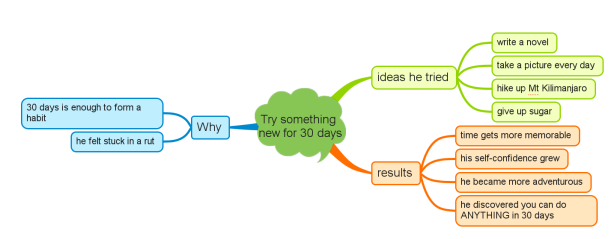

Recently I attended a webinar on encouraging learner autonomy by David Nunan in which he shared a number of case studies from a book they’d published a year ago. One of the stories he shared really brought home for me how important it is for the learners to be helped both with the ideas what to listen to and the tasks – I want to share it here albeit this story goes beyond the topics of listening and using authentic materials with lower levels.

In one of the case studies presented by Nunan Mark Cadd, a researcher, was looking into the problem that many students who come back from a summer abroad don’t seem to have improved their language skills that much. The reason is often that they tended to spend time with other students studying a language but they weren’t interacting with the target community.

So he set up a program in which the learners were required, through 12 contact tasks, to interact with local residents and report her reflection back to the teachers.

Sample task

Task: attend a festival or another public event celebrated in the culture. Speak with at least two members of the culture who are present. Choose two who are quite different, e.g. young vs old, male vs female, etc. Ask why the event is important.Reflection: Which festival, fair, public event etc did you investigate? What is its history? Did you learn anything meaningful about the culture? If so, what? Did you notice any difference between your style of communication and theirs? If so, what were they? Did you have problems understanding them? If so, what did you do about it?

Reflection needed to be posted to a website available to the teacher and other students.

Cadd found that the fact that they were required to do these tasks was initially challenging and scary for the learners, but over time they found that their anxiety lowered and their confidence, fluency and cultural sensitivity improved. Furthermore, they were able to make connections between what they learned in the classroom and the language they were using out of the classroom.

This story made me think of my recent week-long visit to Germany: I love the language but I didn’t practice it at all. I thought how much easier it would be for me to strike up conversations and take advantage of the language environment if I was on a mission to collect evidence for a project – this would not only give me ideas what to look out for and what to talk about, but also serve as a passable conversation starter, and I would feel a lot less self conscious about asking people questions. I think this idea could and should be applied to the wider issue of scaffolding the learners’ interaction with the target culture, whether they live in a country where their target language is spoken, or interact with the culture on the Internet.

If you’d like to provide your learners with a ‘menu’ of resources they could explore out of class, you could find some useful links on this list that the participants of the EVO session complied – but we didn’t work on a menu of autonomous activities.

All in all, I’m extremely grateful to the participants of the #listeningEVO for the wealth of ideas they’ve shared on this topic. There’s everything here I could wish for: from really simple activities to help introduce authentic materials and build the learners’ confidence, to evidence that it’s possible to plunge the learners at the deep end, provided they get scaffolding and that the institution supports this with higher level decisions such as the contents of the exams. Lots to think about and try out in class.

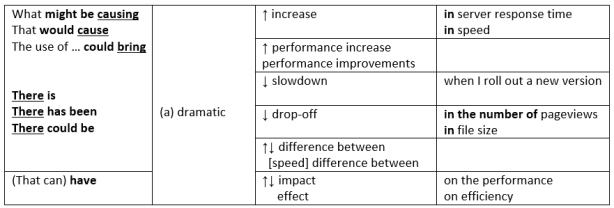

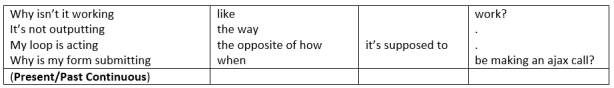

Hit meme types

Hit meme types

I’ve been using the forum for three weeks now and lessons that use this material seem to be giving my students exactly the language they need. Students especially at lower levels find this very motivating. It’s also been a lot of fun for me, because I enjoy exploring the language so much.

I’ve been using the forum for three weeks now and lessons that use this material seem to be giving my students exactly the language they need. Students especially at lower levels find this very motivating. It’s also been a lot of fun for me, because I enjoy exploring the language so much.