What I want to share in this post happened quite a while ago. It wasn’t anything new in terms of teaching methodology and I’m sure a lot of people reading this post will recognize what they do in the classroom. But nevertheless, the experience keeps popping up in my head and I wanted to share it, because it was one of the most positive experiences in my early years of teaching.

This happened when I was teaching in a secondary school. At some point, when my first ever group reached strong B1 level, I bought lots of graded readers, brought the better half of my personal library of English books to the school and launched an extensive reading programme, asking the students to read graded readers and unabridged books three or four times a year. As a follow-up to each round of reading, we did various activities, ranging from book fairs to informal chats, but one thing that stayed the same was that I asked the students to give the book they’d read a rating and write a short review. Another thing that stayed the same was that the majority of students hated writing those reviews.

I was taking British Council Learning Technologies for the Classroom course at the time, and so we started experimenting with some (pretty basic) technology and ended up with an approach to writing which was a whole lot more enjoyable and productive.

1. Creating the sense of audience

The first step was to migrate all writing to the class group on a social network. Instead of asking the students to hand in the reviews in handwritten form, I started creating a dedicated thread where all reviews were to be posted before the deadline (the evening before a lesson). This gave the students a sense of audience and made the activity a lot more authentic. We used a social media site (a Russian analogue of Facebook) because all students had accounts there, but as far as I know, many teachers use other free alternatives, e.g.

- edmodo (a short video tutorial)

- schoology (a short video intro)

- class blogs (P2 wordpress theme that mimics social networks seems to be particularly interesting)

2. Immediate feedback

Since I now got all the reviews before the lesson, I could print them out, mark them in the morning, and then in class the students worked in pairs to edit their contributions on the group page. Apart from the satisfaction of getting feedback immediately after submitting their piece of writing, there were a number of added benefits:

- This gave the students a good reason to submit their work on time, and in general the proportion of students who did writing assignments increased as a result. Also, in my experience with teens, the very fact that everyone in the group can see who has submitted homework encourages students to do it.

- Since I was working with a print-out, I felt at liberty to mark the students’ work more extensively without the fear of ruining it – I now not only used error correction codes to hint at mistakes, but also highlighted all nice turns of phrase that I liked in the students’ writing – so the feedback they received looked a lot more positive.

- Editing itself became a lot easier – no need to rewrite anything and there were no teacher’s comments in the final draft.

3. Autonomous vocabulary learning

One more important tweak was using amazon reviews as a source of language. We did this using scrible – a wonderful tool that allows the user to save any html page to an online library and then annotate it, changing font sizes, highlighting and adding notes:

Source: http://www.scrible.com/tour

A typical assignment looked like this:

_) read a book and give it a rating

a) find a book in a similar genre (google ‘top detective novels’, for instance)

b) read reviews on amazon that give that book the same rating

c) highlight relevant expressions with scrible, _save the page_ and create a permalink to share it

d) write your review using these expressions and _underscoring_ them. Post the review along with the permalink here.

In general, amazon reviews are very well written and are a pleasure to read, and the whole group ended up hunting down some great expressions. Those students who chose to use those expressions (around 75%) were able to use them very aptly in their writing. Here are a couple of samples of my students’ work (big thanks to Ivan Syrovoiskii and Danila Borovkov for allowing me to share them here):

The annotated page: http://scrible.com/s/kx9yM

The review:

On the prowl for something interesting, I happened on Bram Stocker’s Dracula. And when I took an abridged book I actually expected that it wouldl be shortened and generally quite tame in comparison to the original. But what struck me was how they’d oversimplified the whole plot.

I guess almost everyone basicly knows the story – it starts with Jonathan Harker’s arrival to the castle of Count Dracula, the very powerful vampire who’s intimidating the whole of Transylvania. But this edition was so shortened that the whole story of how Jonathan, Arthur and Professor Van Helsing struggled to locate and destroy their nemesis turned just in several pages and the life of vampires which original plot concerns – into several plotlines written in simple English.

In general, I want to say that while I was reading this book I was imbued with the notion that I’m reading just a summary of the original Dracula. On reflection, I reckon I need to add that it might be good as a book for studying English, and it should be treated just as a textbook, without looking at plot.

My overall impression is that if you want to read something interesting – read the original book or don’t read Dracula at all – but don’t bother with abridged books, especially with intermediate level.

The annotated page: http://scrible.com/s/kxpyM

The review:

First of all I have to thank Graham Poll for sharing “Seeing Red” with us. It’s very interesting and a times funny read for people who know something about football and you just can’t put it down.

Every day there are some news about players and managers in the media, but nothing about referees. “Seeing Red” allows you to look behind the scenes of refereeing and to look inside the game.This book shows how young boy, linesman in his father’s match, became the best, world popular referee. I’m sure you will find out something new about referees’ regime, training and how refereeing affects privacy. It also includes many details about famous football players and managers, such as John Terry or David Beckhem or David Moyes. With this book you can participate in famous football matches in many tournaments like World Cup, Premier League or Champions League. After reading I understand how much pressure referees are under, how difficult this thankless but absolutely necessary job is and I have gained a whole bunch of respect for them.

Later on we used all the scrible pages produced by the students to analyze the overall structure of a typical review and put together a google document with useful expressions for talking about characters, plot, the author and so on (a great thing about google documents is that a lot of people can edit the same document simultaneously, so the students worked in pairs, each pair researching a particular aspect of essay writing across everybody’s scribble pages).

While I’m at it, here are some ideas what other genres this approach could be used for:

- writing other types of reviews, e.g. reviewing hotels / gadgets / restaurants / travel destinations / apps (also, specific apps to target a certain vocabulary topic, e.g. apps for health and fitness)/ zoos

- writing replies to an agony aunt column that allows readers to post their suggestions, e.g. http://www.theguardian.com/money/series/dearjeremy (thank you Maria Kachmasheva for sharing this idea)

- similarly, writing replies to questions on forums, Quora or Lifehacker (easily adaptable to an ESP setting)

- researching vocabulary or linkers for exam essays (see an example for ’cause and effect’ and lexical cohesion here: http://scrible.com/s/6f7O0)

- researching vocabulary for comparing trends and describing graphs for IELTS Writing task 1 (e.g. here’s an article on Economist.com packed to the brim language for describing graphs and comparing trends – found by running a quick search using some graph description key words: “plummeted” “rose to” site:economist.com

Closing remarks

As I said at the beginning of this post, a lot of what we ended up doing is standard practice in many language teaching classrooms. However, I still really wanted to share the experience, because for me and my class those tweaks made a lot of difference at the time. They transformed writing assignments from a frustrating chore that the students used to moan about to something that felt good and was a lot more authentic and enjoyable.

And on that note, I must ask: What were some rewarding, happy experiences in your early years of teaching?

Thanks for reading!

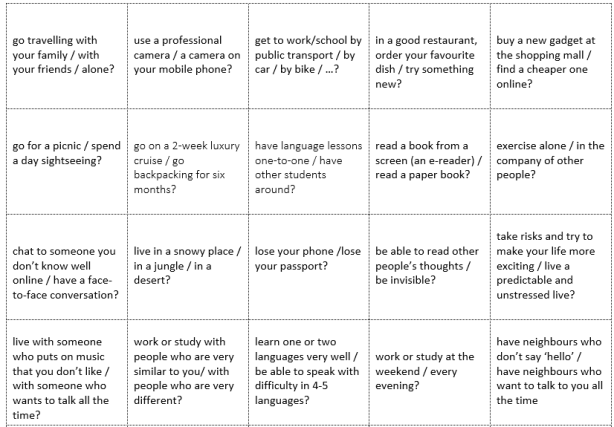

Example: I find it a lot less stressful to get to work by car than to use public transport, because I really dislike the underground. There are just too many people on the train in the morning.

Example: I find it a lot less stressful to get to work by car than to use public transport, because I really dislike the underground. There are just too many people on the train in the morning.